Vasudeva Sarvabhauma Bhattacarya

Continuing the theme of Vāsudeva Sārvabhauma Bhaṭṭācārya (see the beginning in my book On Some Dogmas of the Caitanya Cult in the Light of the Teachings of Madhva)

The king of Orissa (then Kaliṅga) Pratāparudra from the Gajapati dynasty was in conflict and even fought with Kṛṣṇadevarāya, the king of Vijayanagara and Karnataka. Kṛṣṇadevarāya became king in 1510. In the process of the conflict between the two kings, Pratāparudra’s chief paṇḍita, Lolla Lakṣmsīdhara, wrote the Advaita-makaranda, which Pratāparudra sent to Kṛṣṇadevarāya as a philosophical weapon so that Kṛṣṇadevarāya would accept its concept or refute it. The work upholds the teachings of advaita. The famous Advaitin logician Vāsudeva Sārvabhauma Bhaṭṭācārya took part in this philosophical conflict on the side of Pratāparudra. Bhaṭṭācārya wrote a commentary on the Advaita-makaranda at the request of Śrīkūrma Vidyādhara, a minister of Pratāparudra, to whom the commentary is dedicated. In the final commentary stanza, Vāsudeva Sārvabhauma writes about the pride of the king of Karnataka — Kṛṣṇadevarāya and about the great king — the lord of the earth — Pratāparudra, as well as about the great intelligence of Śrīkūrma.

In the commentary on Advaita-makaranda, Vāsudeva Sārvabhauma also talks about his family. Vāsudeva’s grandson Svapneśvara, in the closing stanza of his commentary on the Śāṇḍilya-sūtras, states that his grandfather “was well-known throughout Bengal.” The son of Sārvabhauma, Vāhinīpati, went further — in the commentary on Śabdāloka, he proclaims his father an avatāra of Viṣṇu.

The philosophical conflict of the kings, according to one source, occurred after the conversion of Vāsudeva Sārvabhauma to Caitanya’s Vaiṣṇavism, which indicates the fictitious plot of the conversion in the Caitanya-caritāmṛta. For others, before conversion. According to Dinesh Chandra Bhattacharya (see Vāsudeva Sārvabhauma, Indian Historical Quarterly 16, 1940), Kṛṣṇadevarāya’s military campaign against Orissa began in 1512, and Sārvabhauma probably wrote a commentary on Advaita-makaranda in 1511. In 1510–1512 Caitanya was on a pilgrimage in South India. Dinesh Chandra notes that the history of Vāsudeva’s conversion to Vaiṣṇavism is rather controversial (p. 66). Neither the son nor the grandson of Vāsudeva Sārvabhauma showed the slightest attachment to Bengal Vaiṣṇavism of Caitanya in their works, as far as it was possible. Independent descriptions of the life of Vāsudeva Sārvabhauma by authors who are not related to Caitanya and his religion speak of Vāsudeva as an orthodox scholar, Advaitin and logician. All this once again makes one doubt the historicity of Vāsudeva Sārvabhauma’s conversion to Vaiṣṇavism, or at least believe that the nature of the so-called conversion of Sārvabhauma by Caitanya really was as deep and permanent as Caitanya’s biographers try to show (p. 69).

Sārvabhauma left Purī before Caitanya’s death. Kavikarṇapūra writes about this in Caitanya-candrodaya. Sārvabhauma survived Caitanya and spent his last days in Vārānasī, as was the custom with pious Bengali scholars.

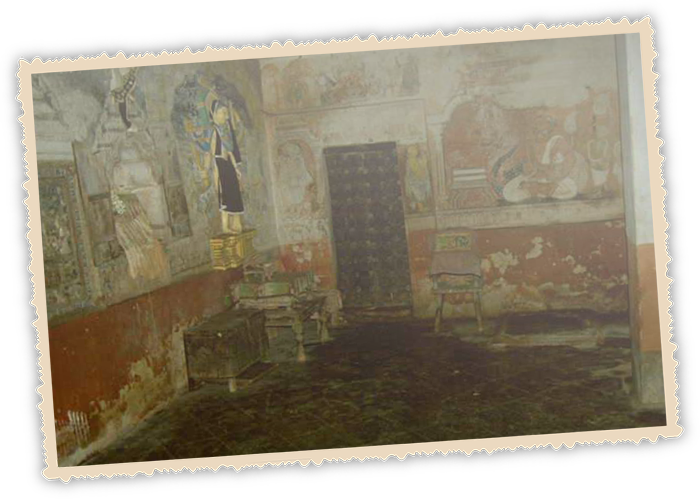

Despite the claims of some residents of the city of Purī that they are descendants of Vāsudeva Sārvabhauma, today there is not a single family that can accurately present their genealogy from Sārvabhauma. With one of these families, more precisely with a brahmin of about 30 years old, I met in 2001 in Purī, in the supposed house of Vāsudeva Sārvabhauma. There is no evidence that the famous logician lived in this house.

Tradition states that Bhaṭṭācārya had four prominent disciples: Caitanya, Raghunātha Śiromaṇi (1460–1540, one of the six gosvāmins of Vrindavan), Raghunandana and Kṛṣṇānanda. We only know for certain that it was Raghunātha who was such. The other three are legend, apart from Caitanya’s brief visit in 1510 to several of Vāsudeva’s lessons. The Navadvīpa-born Sārvabhauma Bhaṭṭācārya developed Navya-Nyāya in this city.