Diksha in the Chaitanya Tradition: Authority and Lineage — Part 4

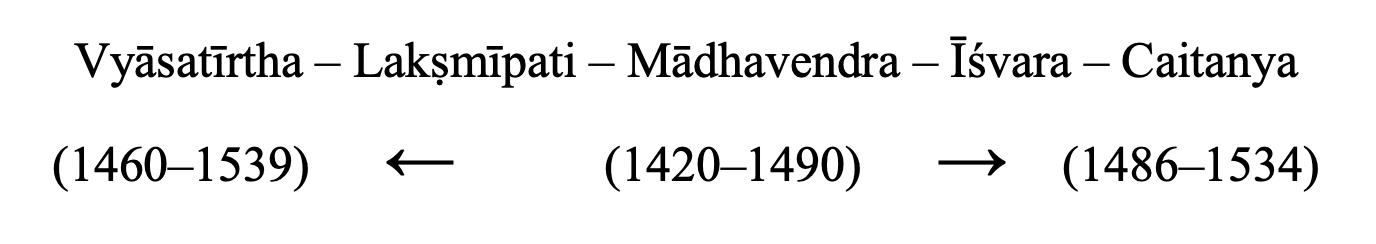

The makers of the Gauḍīya-Paramparā did not take into account the years of life of the personalities integrated in the paramparā. Between Vyāsatīrtha and Caitanya in the paramparā there are three more links — three lives — Lakṣmīpati, Mādhavendra Purī, Īśvara Purī. The years of Mādhavendra’s life are 1420–1490. According to Gauḍīya tradition, Mādhavendra died when Caitanya was a child.

Caitanya was born in 1486 and Vyāsatīrtha in 1460 (d. 1539) — they are contemporaries, a difference in age of only 26 years, and this fact makes it physically impossible for the paramparā presented by the Gauḍīyas to prove the connection of their school with the Madhva tradition, because it is impossible for a peer of Caitanya — Vyāsatīrtha, have a disciple (Lakṣmīpati) who then had his own disciple (Mādhavendra) who in turn became famous somewhere outside the Madhva school and who had his own disciples, one of whom was Caitanya’s dīkṣā-guru.

Mādhavendra died when Caitanya was a child. And Vyāsatīrtha himself was a contemporary of Caitanya. How can there be three links between Vyāsatīrtha and Caitanya — three lives, three personalities? It is physically impossible.

Caitanya received dīkṣā from Īśvara Purī when he was 17 years old = 1503. Suppose Mādhavendra received dīkṣā from Lakṣmīpati also when he was 17 years old = 1437, or even when he was 10 years old = 1430 (for the sake of accuracy). At this time Vyāsatīrtha was not even born, let alone Lakṣmīpati received dīkṣā from him, became a disciple, learnt, and then passed the dīkṣā on to Mādhavendra. Does not clash at the best and most favourable calculation for the Gauḍīyas and with the most inconvenient one for the Madhvaites.

In 16–17 years = 1476–1477. Vyāsatīrtha had just finished the traditional school and was not yet an ācārya of the Madhva-Paramparā. Around this period, he became a sannyāsī and lived under his guru, Brahmaṇya Tīrtha, who died in 1476. In 1478, Vyāsatīrtha began to represent the paramparā of his guru and went to Kanci to study. After many years of study in Kanci, Vyāsatīrtha went to Mulbagal to Śrīpādarāja and stayed there for 6 years.

Even if we reduce the “many years” in Kanci to 5, although it was probably longer, he spent until 1483 in Kanci, after which he spent another six years in Mulbagal. Total: 1489.

There he took charge of one of the maṭhas of the Madhva school. Mādhavendra died in 1490. And before Mādhavendra, there was still to be Lakṣmīpati. And yet Vyāsatīrtha was a contemporary of Caitanya. How can three lives of three persons fit between two contemporaries?

When I speak of the Madhva school, using the words “master”/“guru” in the context of paramparā, I am not referring to dīkṣā, but to initiation into sannyāsa, which is a different story. Vyāsatīrtha may have had disciples, but not in the Gauḍīya sense through dīkṣā by gopāla-mantra.

Between Vyāsatīrtha and Caitanya, if the paramparā was correct and we did not know that Mādhavendra died when Caitanya was a child, it would be difficult to assert anything, but we have events and life descriptions from Gauḍīya sources that prove the paramparā of Caitanya’s school to be fake.

If the paramparā is fake, the mantra is fake and inauthentic, can everything else be a working authority, so to speak, with Caitanya’s followers themselves insisting on adherence to paramparā and dīkṣā?

In the Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇava literature it does not appear that Caitanya himself knew about Vyāsatīrtha. The impression is that he did not know at all. Nowhere is there even a hint that Caitanya had even heard of Vyāsatīrtha. Although Vyāsatīrtha was quite a well-known person in the circles of intellectuals and leading temples of the time, in Kanci, in Tirupati, Vijayanagara etc., where he was the chief priest and one of the king’s advisors on śāstras and dharma.

How can three persons who became links in the succession and died by the time of Caitanya’s birth and childhood be put in the paramparā between Vyāsatīrtha and Caitanya, yet Vyāsatīrtha and Caitanya lived at the same time?

In Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇavism, traditionally, it is customary to lead a paramparā, or rather continue, after the death of one’s guru. If Lakṣmīpati and Mādhavendra died, how could Vyāsatīrtha be the same age as Caitanya, if one takes the Gauḍīya-Paramparā at face value?

It is important to know, there are not many sannyāsīs in Tattvavāda. Sannyāsa is not given out right and left. If a person accepts sannyāsa, he lives in maṭha. Everyone knows him. He may not head the maṭha until the previous sannyāsī-ācārya dies. All the sannyāsīs are counted, but there is no dīkṣā. So how could Lakṣmīpati become the sannyāsa-successor to Vyāsatīrtha if there was no sannyāsī named Lakṣmīpati in any madhva-maṭhas in the period 1539?

There are other strong arguments in favour of the Caitanya’s guru-paramparā being a late period forgery and that the Caitanya school is not part of the Madhva-Sampradāya and never was, and is therefore inauthentic and without any roots (sampradāya-less).

Caitanya in the Caitanya-caritāmṛta 2.9.245–276 makes a distinction between the Gauḍīya-Vaiṣṇavas and the followers of Madhva (Tattvavādīs): “Caitanya Mahāprabhu next arrived at Uḍupī, the place of Madhvācārya, where the philosophers known as Tattvavādīs resided.” “To date, the followers of Madhvācārya, known as Tattvavādīs, worship this Deity.” “When the Tattvavādī Vaiṣṇavas first saw Śrī Caitanya Mahāprabhu, they considered Him a Māyāvādī sannyāsī.” “Śrī Caitanya Mahāprabhu could understand that the Tattvavādīs were very proud of their Vaiṣṇavism.” “The chief ācārya of the Tattvavāda community was very learned in the revealed scriptures.”

In the Caitanya-caritāmṛta 2.9.276–277, Caitanya twice says to His opponent “your sampradāya” (tomāra sampradāye). Isn’t the very idea of Caitanya’s disputation with the followers of Madhva, as described in the Caitanya-caritāmṛta, an open ideological confrontation?

All of the above and the examples given indicate that Caitanya did not associate himself with the Madhva-Sampradāya either doctrinally or formally.

“I have seen many Vaiṣṇavas [in the south], but they are all worshippers of Nārāyaṇa; there were also Tattvavādīs among them, but they are exactly the same, their philosophy imperfect. Others were worshippers of Śiva. A large number of heretics. But, Sārvabhauma, only the views of Rāmānandarāya are really interesting to me” (Caitanya-chandrodaya-nāṭaka, 8).

The dīkṣā-mantra — received by the Gauḍīyas not just outside the authoritative sampradāya, but even outside any sampradāya and it is not clear how it became the dīkṣā-mantra of an entire school. After all, someone must have questioned Mādhavendra as to who he was and where he came from, besides being an advaita-sannyāsī. Why then does an advaita-sannyāsī not have an advaita-dīkṣā or dīkṣā-mantra and is it normal that no school at that time had such a dīkṣā-mantra like Gauḍīyas have?

The dīkṣā of the Gauḍīya school is barren and dīkṣā-mantra is fruitless. It does not work and apparently will not lead to Kṛṣṇa. Kṛṣṇa Himself emphasises the importance of guru-paramparā in the Gītā. No matter how much you repeat it, it won’t do any good. The quotation from the Padma-purāṇa confirms this.

The makers of the Gauḍīya-Paramparā did not take into account the years of life of the personalities integrated in the paramparā. Between Vyāsatīrtha and Caitanya in the paramparā there are three more links — three lives — Lakṣmīpati, Mādhavendra Purī, Īśvara Purī. The years of Mādhavendra’s life are 1420–1490. According to Gauḍīya tradition, Mādhavendra died when Caitanya was a child.

Caitanya was born in 1486 and Vyāsatīrtha in 1460 (d. 1539) — they are contemporaries, a difference in age of only 26 years, and this fact makes it physically impossible for the paramparā presented by the Gauḍīyas to prove the connection of their school with the Madhva tradition, because it is impossible for a peer of Caitanya — Vyāsatīrtha, have a disciple (Lakṣmīpati) who then had his own disciple (Mādhavendra) who in turn became famous somewhere outside the Madhva school and who had his own disciples, one of whom was Caitanya’s dīkṣā-guru.

Mādhavendra died when Caitanya was a child. And Vyāsatīrtha himself was a contemporary of Caitanya. How can there be three links between Vyāsatīrtha and Caitanya — three lives, three personalities? It is physically impossible.

Caitanya received dīkṣā from Īśvara Purī when he was 17 years old = 1503. Suppose Mādhavendra received dīkṣā from Lakṣmīpati also when he was 17 years old = 1437, or even when he was 10 years old = 1430 (for the sake of accuracy). At this time Vyāsatīrtha was not even born, let alone Lakṣmīpati received dīkṣā from him, became a disciple, learnt, and then passed the dīkṣā on to Mādhavendra. Does not clash at the best and most favourable calculation for the Gauḍīyas and with the most inconvenient one for the Madhvaites.

In 16–17 years = 1476–1477. Vyāsatīrtha had just finished the traditional school and was not yet an ācārya of the Madhva-Paramparā. Around this period, he became a sannyāsī and lived under his guru, Brahmaṇya Tīrtha, who died in 1476. In 1478, Vyāsatīrtha began to represent the paramparā of his guru and went to Kanci to study. After many years of study in Kanci, Vyāsatīrtha went to Mulbagal to Śrīpādarāja and stayed there for 6 years.

Even if we reduce the “many years” in Kanci to 5, although it was probably longer, he spent until 1483 in Kanci, after which he spent another six years in Mulbagal. Total: 1489.

There he took charge of one of the maṭhas of the Madhva school. Mādhavendra died in 1490. And before Mādhavendra, there was still to be Lakṣmīpati. And yet Vyāsatīrtha was a contemporary of Caitanya. How can three lives of three persons fit between two contemporaries?

When I speak of the Madhva school, using the words “master”/“guru” in the context of paramparā, I am not referring to dīkṣā, but to initiation into sannyāsa, which is a different story. Vyāsatīrtha may have had disciples, but not in the Gauḍīya sense through dīkṣā by gopāla-mantra.

Between Vyāsatīrtha and Caitanya, if the paramparā was correct and we did not know that Mādhavendra died when Caitanya was a child, it would be difficult to assert anything, but we have events and life descriptions from Gauḍīya sources that prove the paramparā of Caitanya’s school to be fake.

If the paramparā is fake, the mantra is fake and inauthentic, can everything else be a working authority, so to speak, with Caitanya’s followers themselves insisting on adherence to paramparā and dīkṣā?

In the Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇava literature it does not appear that Caitanya himself knew about Vyāsatīrtha. The impression is that he did not know at all. Nowhere is there even a hint that Caitanya had even heard of Vyāsatīrtha. Although Vyāsatīrtha was quite a well-known person in the circles of intellectuals and leading temples of the time, in Kanci, in Tirupati, Vijayanagara etc., where he was the chief priest and one of the king’s advisors on śāstras and dharma.

How can three persons who became links in the succession and died by the time of Caitanya’s birth and childhood be put in the paramparā between Vyāsatīrtha and Caitanya, yet Vyāsatīrtha and Caitanya lived at the same time?

In Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇavism, traditionally, it is customary to lead a paramparā, or rather continue, after the death of one’s guru. If Lakṣmīpati and Mādhavendra died, how could Vyāsatīrtha be the same age as Caitanya, if one takes the Gauḍīya-Paramparā at face value?

It is important to know, there are not many sannyāsīs in Tattvavāda. Sannyāsa is not given out right and left. If a person accepts sannyāsa, he lives in maṭha. Everyone knows him. He may not head the maṭha until the previous sannyāsī-ācārya dies. All the sannyāsīs are counted, but there is no dīkṣā. So how could Lakṣmīpati become the sannyāsa-successor to Vyāsatīrtha if there was no sannyāsī named Lakṣmīpati in any madhva-maṭhas in the period 1539?

There are other strong arguments in favour of the Caitanya’s guru-paramparā being a late period forgery and that the Caitanya school is not part of the Madhva-Sampradāya and never was, and is therefore inauthentic and without any roots (sampradāya-less).

Caitanya in the Caitanya-caritāmṛta 2.9.245–276 makes a distinction between the Gauḍīya-Vaiṣṇavas and the followers of Madhva (Tattvavādīs): “Caitanya Mahāprabhu next arrived at Uḍupī, the place of Madhvācārya, where the philosophers known as Tattvavādīs resided.” “To date, the followers of Madhvācārya, known as Tattvavādīs, worship this Deity.” “When the Tattvavādī Vaiṣṇavas first saw Śrī Caitanya Mahāprabhu, they considered Him a Māyāvādī sannyāsī.” “Śrī Caitanya Mahāprabhu could understand that the Tattvavādīs were very proud of their Vaiṣṇavism.” “The chief ācārya of the Tattvavāda community was very learned in the revealed scriptures.”

In the Caitanya-caritāmṛta 2.9.276–277, Caitanya twice says to His opponent “your sampradāya” (tomāra sampradāye). Isn’t the very idea of Caitanya’s disputation with the followers of Madhva, as described in the Caitanya-caritāmṛta, an open ideological confrontation?

All of the above and the examples given indicate that Caitanya did not associate himself with the Madhva-Sampradāya either doctrinally or formally.

“I have seen many Vaiṣṇavas [in the south], but they are all worshippers of Nārāyaṇa; there were also Tattvavādīs among them, but they are exactly the same, their philosophy imperfect. Others were worshippers of Śiva. A large number of heretics. But, Sārvabhauma, only the views of Rāmānandarāya are really interesting to me” (Caitanya-chandrodaya-nāṭaka, 8).

The dīkṣā-mantra — received by the Gauḍīyas not just outside the authoritative sampradāya, but even outside any sampradāya and it is not clear how it became the dīkṣā-mantra of an entire school. After all, someone must have questioned Mādhavendra as to who he was and where he came from, besides being an advaita-sannyāsī. Why then does an advaita-sannyāsī not have an advaita-dīkṣā or dīkṣā-mantra and is it normal that no school at that time had such a dīkṣā-mantra like Gauḍīyas have?

The dīkṣā of the Gauḍīya school is barren and dīkṣā-mantra is fruitless. It does not work and apparently will not lead to Kṛṣṇa. Kṛṣṇa Himself emphasises the importance of guru-paramparā in the Gītā. No matter how much you repeat it, it won’t do any good. The quotation from the Padma-purāṇa confirms this.