Prophecies of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu: A Comprehensive Analysis — Part 6

In 1865, a Sanskrit treatise, The Nárada Pancha Rátra in original Sanscrit, was introduced in the Bibliotheca Indica series under No. 38. The editor of the treatise was Professor K.M. Banerjea from Calcutta. In the preface to the work (pp. 3–9) Banerjea wrote: “One of the oldest, if not the earliest, specimen of Vaiṣṇava literature in Sanskrit… The only work that can challenge the palm of primacy is the Bhágavata-purána.”

There were three expositions of the work in the following decades. The work was translated into Bengali in prose and verse. In 1921, the work was translated into English.

In fact, the treatise turned out to be not so ancient as Banerjea thought and assured his readers. The Nárada Pancha Rátra in original Sanscrit published by Banerjea was first studied by R.G. Bhandarkar:

In 1865, a Sanskrit treatise, The Nárada Pancha Rátra in original Sanscrit, was introduced in the Bibliotheca Indica series under No. 38. The editor of the treatise was Professor K.M. Banerjea from Calcutta. In the preface to the work (pp. 3–9) Banerjea wrote: “One of the oldest, if not the earliest, specimen of Vaiṣṇava literature in Sanskrit… The only work that can challenge the palm of primacy is the Bhágavata-purána.”

There were three expositions of the work in the following decades. The work was translated into Bengali in prose and verse. In 1921, the work was translated into English.

In fact, the treatise turned out to be not so ancient as Banerjea thought and assured his readers. The Nárada Pancha Rátra in original Sanscrit published by Banerjea was first studied by R.G. Bhandarkar:

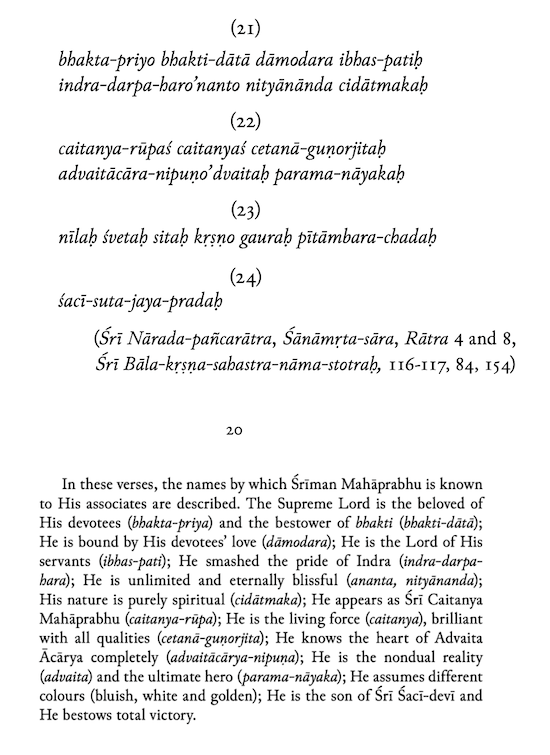

This work praises Krishna and Radha, the best of the women whom Krishna loved… The elevation of Radha to the status of Krishna’s eternal companion is one of the main aims of this Samhita. But the work does not mention Vyuhas, which constitute a feature of the Pancharatra tradition. The ideas presented in the treatise are exactly the same as the religious views of Vallabhacharya. The Samhita was probably written shortly before Vallabha, i.e. around the beginning of the sixteenth century. Ramanuja’s followers regard the treatise as apocryphal.”To add to Bhandarkar’s words, the Nārada-pañcarātra is not considered an authoritative treatise by Madhva’s followers either, nor did Madhva himself ever mention it or refer to it. Bhandarkar’s view was also supported by Otto Schrader, a major expert on Pañcarātra and its literature. There is another work, or rather quotations, called Nārada-pañcarātra, which we find among medieval authors, including Caitanya’s followers. The work is often quoted in Dharmaśāstras composed in Northeast India, Bengal and Orissa. None of these quotations are found in The Nárada Pancha Rátra in original Sanscrit, published by K.M. Banerjea. The two works also differ in poetic metre. Madhvacharya’s followers consider both works to be apocryphal, unrelated to the ancient Pañcarātra Saṃhitās. Let us turn to Bengal. Gopāla Bhaṭṭa, one of the early ācārya-s of the Caitanya school, in his monumental work the Haribhaktivilāsa (written before 1541) quotes over thirty stanzas from the Nārada-pañcarātra. Some of which are quite long. About two-thirds of the quotations are in the first eight vilāsa-s: 1.94, 96; 1.101; 1.115; 1.130–134, etc. Rūpa Gosvāmin in the Bhakti-rasāmṛta-sindhu (completed in 1541) quotes the Nārada-pañcarātra four times. The most prolific and versatile theologian of the Caitanya sampradāya, Jīva Gosvāmin, in Ṣaṭsandarbha quotes Nārada-pañcarātra nineteen times. Banerjea prepared an edition of The Nárada Pancha Rátra in original Sanscrit based on manuscripts available in Bengal, but we do not find a single passage from it in the quotations used in the seminal works of the Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇavas. All this clearly shows that Gopāla Bhaṭṭa, Rūpa Gosvāmin, Jīva Gosvāmin, and other authors of the Gauḍīya sampradāya, ending with Sadāśiva, had in mind an entirely different work with the same title, the Nārada-pañcarātra. But like the one published by Banerjea, the “Gauḍīya” Nārada-pañcarātra is for the followers of Madhva an apocryphal work praising the heretical deity Rādhā. The Nárada Pancha Rátra consists of five sections called rātra-s. The core of the work is the 3rd rātra. It describes the mode of worship of Gopāla-Kṛṣṇa. Rādhā, the original śakti (2.6.7–32), the eternal consort of Kṛṣṇa and mother of Viṣṇu (2.3.40), is not mentioned at all in this rātra in connection with the worship of Kṛṣṇa. Instead of Rādhā, Rukmiṇī, Satyabhāmā and other legitimate wives of Kṛṣṇa are mentioned. Most importantly, the 3rd rātra is a verbatim reproduction of the first seven paṭala-s of the Kramadīpikā of Keśava Bhaṭṭa of Kashmir (aka Keśava Kāśmīrī in the Caitanya-caritāmṛta). Keśava Bhaṭṭa was the head of the Nimbārka school and the author of several famous works: a commentary on the Bhagavad-gītā, a commentary on Śrīnivāsa’s Kaustubha (commentary to Nimbārka’s Vedānta-pārijāta), etc. Kramadīpikā is a unique work on Kṛṣṇa worship written in the early fifteenth century. In North Indian Vaiṣṇavism, Kramadīpikā is considered an authoritative treatise. The introduction of Kramadīpikā into the main body of the Nárada Pancha Rátra is a clear example of plagiarism. The only originality that can be recognized for the plagiarist is that he composed the first ten stanzas of the first chapter as an introduction (Śiva narrates the Kramadīpikā at the request of Pārvatī); made an effort to make 19 chapters out of the 8 paṭala-s of the Kramadīpikā; and brought out the tantric aspect of Kṛṣṇa-pūjā in the 5th rātra. In 1450, several decades later, Vrajeśācārya wrote a commentary on the Kramadīpikā. And this fact refutes another myth about Caitanya’s victory over yet another opponent. It is about young Caitanya’s disputation with paṇḍita Keśava Kāśmīrī and Keśava’s “defeat”. The story is told in the Caitanya-caritāmṛta 1.16.28–108. The real Keśava Kāśmīrī lived almost 70 years before Caitanya was born and could not have met him. This story has no historical basis. Another Gauḍīya myth in the service of creating a new god. Two internal testimonies in the text of the Nárada Pancha Rátra, which escaped Bhandarkar’s attention, prove conclusively that the work could not have originated before the moment Caitanya was recognised as an incarnation of Kṛṣṇa, which, from the beginning of his preaching career, Caitanya was not yet considered to be. In Chapter 8 of Part Five (5.8.15), in listing and explaining the most important of Kṛṣṇa’s names (and qualities), the name “Caitanya” is mentioned. It ranks with the other names of Kṛṣṇa: Keśava, Madhava, etc.: